Framework for Chief Compliance Officer Liability in the Financial Sector

INTRODUCTION

For several years now, chief compliance officers (CCOs) in the financial sector have voiced a sustained tide of concern, detailed in the New York City Bar Association Compliance Committee’s (Compliance Committee) February 2020 report on Chief Compliance Officer Liability in the Financial Sector (Report), from increased enforcement actions holding CCOs personally liable, in particular for actions that do not result from fraud or obstruction on their part. These career-ending enforcement actions discourage individuals from becoming or remaining compliance officers and performing vital functions that regulators stretched too thin would otherwise be unable to perform, particularly when other options, such as providing legal advice or becoming an outside compliance service provider or businessperson, involve less personal risk.

In response to this concern, numerous U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Commissioners and Staff members, including Commissioner Hester Peirce in multiple speeches, Division of Examinations Director Peter Driscoll, Co-Chief of the Asset Management Unit of the Division of Enforcement Adam Aderton, former Director of the New York Regional Office of the SEC and former Acting Director of the Division of Enforcement Marc Berger, former Commissioner Daniel Gallagher, and former Director of the Division of Enforcement Andrew Ceresney, have repeatedly discussed the issue in public speeches and conference appearances and attempted to offer comfort and guidance. Several Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) executives have also discussed the matter in public appearances, including Executive Vice President and Head of Enforcement Jessica Hopper.

While regulators are paying increased attention to the compliance function, we believe that the creation of a formalized regulatory framework (Framework) describing nonbinding factors for the SEC to consider in determining whether to charge a CCO is a crucial next step to providing the enforcement clarity CCOs seek. Notably, in an October 2020 speech before the National Society of Compliance Professionals, Peirce called for the creation of such a Framework, which is consistent with recommendations we made in the Report.

The Compliance Committee, in partnership with the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, the American Investment Council, and the Association for Corporate Growth, submits this proposal of nonbinding factors for the SEC to consider in creating a Framework under which to evaluate whether to bring charges against CCOs for conduct relating to their compliance-related duties (CCO Conduct Charges) under the federal securities laws.[1] Many of the factors in our proposed Framework are likely already used to some extent in decisions regarding whether to prosecute, but we believe that formalizing such factors will help provide clear guidance to CCOs and enable them to confidently engage in their necessary work. We also believe that a Framework will be useful and necessary to all enforcement philosophies, given how much CCOs help extend regulatory resources. By instituting a Framework, the SEC and the compliance industry will more fully realize their shared interests which, in turn, will ultimately benefit the investing public.

There is significant precedent for such a Framework. As noted in the Report, other regulatory bodies, such as the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), have similar frameworks, and existing guidance largely outlines substantive areas of focus for a compliance department rather than the potential liability of an individual CCO. Offers of support that the SEC may punish the employer if it does not support the CCO are of little comfort for CCOs whose employment prospects will also be deeply damaged by any enforcement case against an employer where they worked.

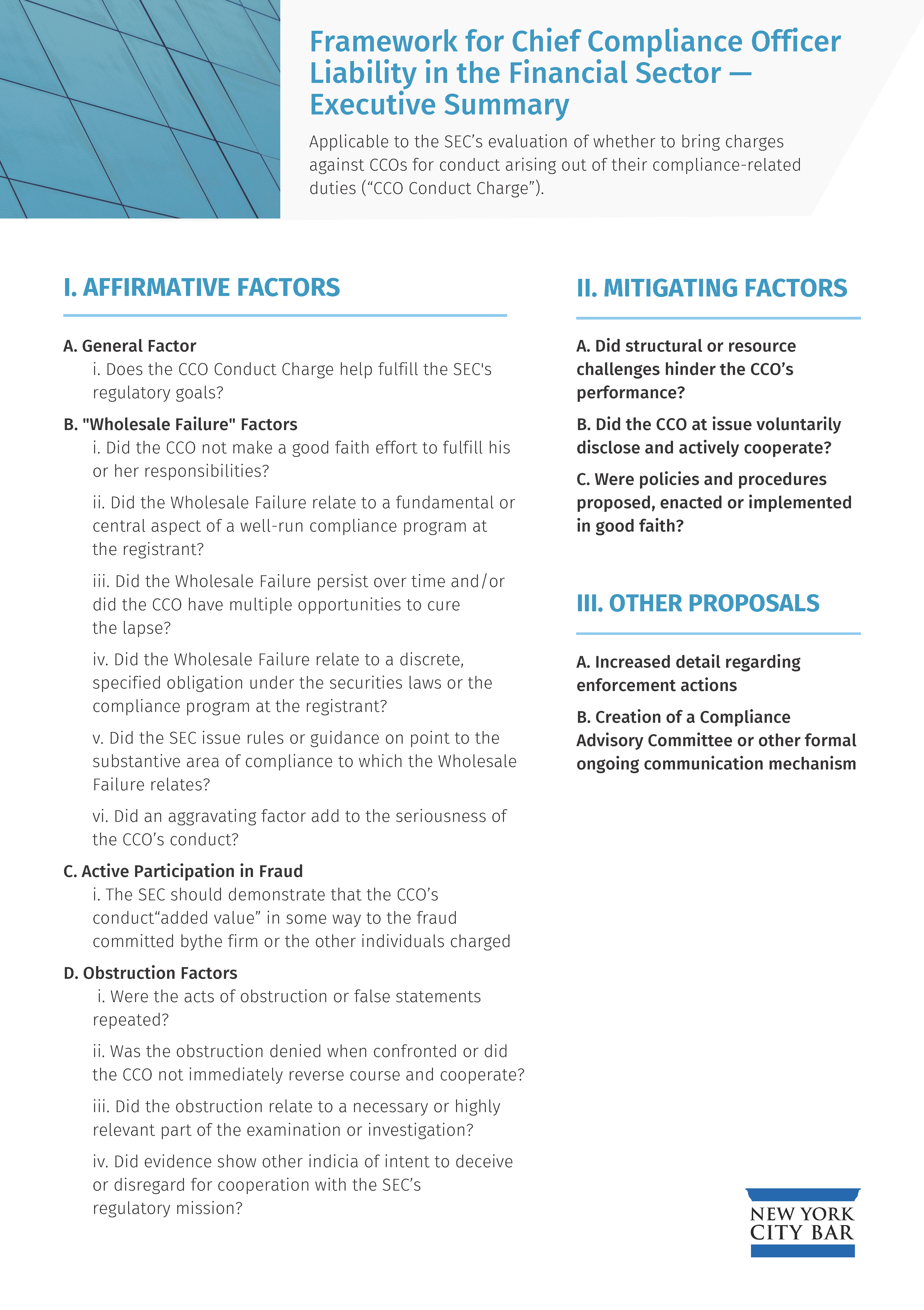

In proposing these factors, we fully appreciate that each situation is unique. Given the special role that CCOs play and the compliance community’s legitimate concerns, we believe that instituting a Framework of nonbinding factors will provide the compliance community with the guidance it needs balanced against regulators’ need for ultimate discretion. We first discuss affirmative factors that should be present to bring a charge, and then list mitigating factors that, if present, should weigh against a CCO Conduct Charge.

AFFIRMATIVE FACTORS

We first discuss one factor that we believe should be considered in all CCO Conduct Charges. Next, we note factors relevant to specific types of CCO Conduct Charges – namely, those relevant to a claim that a CCO had exhibited a “wholesale failure” to carry out responsibilities, a claim that a CCO participated directly in fraud and an allegation of obstruction, in turn.

General Factor

Does the CCO Conduct Charge help fulfill the SEC’s regulatory goals?

We believe that, each time the SEC considers a CCO Conduct Charge, it should carefully consider whether the charge helps the SEC fulfill its ultimate regulatory goals.[2] Prosecutorial discretion is fundamental to a regulatory mission, and as Commissioner Peirce noted in her speech on CCO liability, “[j]ust because the Commission can do something under our rules does not mean that we should do it.”[3] In many circumstances, we believe that CCO Conduct Charges will fail to advance the interests of protecting the capital markets and investors.

One primary goal of enforcement is deterrence, but we believe that CCO Conduct Charges do not meaningfully deter CCOs from future inappropriate conduct. CCOs operate under a unique regulatory regime and unique structural constraints. The system designates CCOs as personally responsible for something – securities law compliance at their firms – that is ultimately determined by other human beings whom the CCO cannot control and, as a cost center, is poorly suited to do so. CCOs do not have any special anti-retaliation protection beyond standard whistleblower laws available to everyone and that do not apply to internal reporting, and the system does not provide for any minimum number of resources required to be provided to the CCO. Despite this structure, CCOs must still make yes or no decisions, frequently in real time with limited guidance from regulators and relatively limited factual clarity. We believe that these constraints, directly or indirectly, result in many of the errors in judgment or even purposeful or neglectful conduct that enforcement actions are brought against. The most efficient way to deter problematic practices by CCOs is to devise mechanisms to eliminate or at least mitigate these constraints.

If anything, we believe that CCO Conduct Charges may potentially increase future securities law violations for two reasons. First, liability for CCO Conduct Charges perpetuates a misperception that the SEC is targeting CCOs, which, in turn, may result in CCOs leaving the profession for adjacent positions such as compliance consulting, providing legal advice or dealmaking. Regulators have protested to strong effect that they are not targeting CCOs and are only punishing the worst actors. However, CCOs remain concerned because the system that the SEC has created, with individual accountability for compliance, has uniquely placed CCOs in the “firing line” of being charged, above and beyond all other employees and partners of a financial firm. The system requires an individual CCO to ensure adherence to the compliance program that is itself only secondarily geared to ensure compliance with the securities laws, as opposed to other laws, such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), which does not require the designation of an individual CCO.

Second, enforcement actions increase anxiety for many earnest CCOs and cause them to withdraw from the type of deep involvement in the organization that regulators prefer. As the Director of the Division of Examinations Pete Driscoll noted in a November 2020 speech, CCOs prevent numerous violations of the securities laws, and regulators would be stretched far too thin if their capabilities were not supplemented in this way.[4] Thus, we believe that the SEC’s regulatory mission would be better fulfilled at times by declining to issue an enforcement action. The SEC can still resolve the conduct underlying many CCO Conduct Charges via a deficiency letter or another nonpublic resolution, in the same way that much conduct by non-CCOs is resolved.

To be clear, we do not mean to imply that CCO Conduct Charges should never be brought. Moreover, the negative policy consequences described above are more likely to occur when the underlying conduct is only debatably inappropriate, while wildly inappropriate conduct is more understood by the profession and the industry and less likely to result in negative consequences for the SEC and investors. We only argue that the SEC should have a slightly higher standard for charging CCOs than against a registrant or a businessperson.

Wholesale Failure Factors

As many parties have acknowledged, it is the third type of case brought against CCOs – that framed by the SEC as when a CCO “exhibited wholesale failures in carrying out responsibilities that were clearly assigned to them” or that the CCO “fails meaningfully to implement compliance programs, policies[]and procedures for which he or she has direct responsibility”[5] – that the compliance community finds the most concerning. It is the enforcement cases brought based on this prong that are most likely to result in CCOs leaving the profession or practicing defensively. We believe that discretion based on this prong should be judiciously exercised and rigorously explained in the enforcement order and in remarks from Commissioners and Staff members.

As part of that judicious discretion, we believe that the SEC should conclude that the factors below were present prior to charging a CCO related to a failure under this prong (a Wholesale Failure).

Did the CCO not make a good faith effort to fulfill his or her responsibilities?

This factor is largely a restatement of the existing statement from the SEC that “good faith judgments of CCOs made after reasonable inquiry and analysis should not be second guessed.”[6] However, some cases brought against CCOs under this prong, without more explanation, appear to involve situations where the CCO did make some good faith effort to raise concerns to others or remedy the underlying situation, however incompletely or ultimately unsuccessfully.[7]

Did the Wholesale Failure relate to a fundamental or central aspect of a well-run compliance program at the registrant?

Compliance is a complex area and CCOs have numerous duties they must either fulfill personally or supervise, whether under the securities laws and relevant judicial precedent, SEC rules and regulations, SEC guidance, or registrant compliance manual requirements. While registrants, supervised persons at registrants and CCOs alike must seek to obey all compliance requirements, lapses do happen. While the SEC occasionally brings enforcement actions against registrants and supervised persons relating to a wide variety of lapses, most such actions relate to extremely important aspects of compliance, such as fulfillment of a fiduciary duty, failing to disclose fees and expenses or conflicts of interest, or other cases involving monetary impact to investors or clients. We believe that, in the realm of CCO liability, the Framework should limit liability to Wholesale Failures that involve such highly relevant and important matters. While a robust enforcement Framework, in the style of a “broken windows” philosophy of policing, may help deter securities laws violations (a matter on which we express no opinion), as explained above, we believe that extending such a philosophy to CCO liability would actually exacerbate and not deter such violations.

While we understand that the Thaddeus North case involved the SEC approving a FINRA order and was not subject to the same standards as a native SEC enforcement order, we believe that the matter is a good example of where, without more explanation, CCO liability may not have fulfilled this requirement. North largely related to allegations that the CCO failed to fulfill their responsibilities – clearly required by FINRA rules for broker-dealers and generally accepted as a good practice by all SEC registrants – to review electronic messages. Electronic messaging review is something that CCOs do need to perform, but again, without more, we do not believe that this function is central enough to a compliance program that CCO liability should typically attach with all the negative potential consequences that occur when such liability is raised.[8]

Did the Wholesale Failure persist over time and /or did the CCO have multiple opportunities to cure the lapse?

As noted in the Report, CCOs must frequently make important decisions in real time with limited guidance. The anxiety in the compliance community from liability cases stems in large part from their realization of the need for such decisions as part of being a compliance officer. As such, we believe that in fulfilling the SEC’s stated aversion to issuing enforcement actions against CCOs for good faith decisions, those enforcement actions most properly lie where the Wholesale Failures took place over long periods of time or the CCOs in question had multiple occasions to cure them. To this point, in one enforcement action against a CCO, the SEC alleged that the custody rule violations at issue had been raised to the firm more than a decade prior and had previously been the subject of a separate enforcement action against the firm several years before the SEC also charged the CCO in a second enforcement action.[9]

Did the Wholesale Failure relate to a discrete, specified obligation under the securities laws or the compliance program at the registrant?

Did the SEC issue rules or guidance on point to the substantive area of compliance to which the Wholesale Failure relates?

As we noted in the Report, CCOs interpreting laws or rules about which reasonable minds can differ – or laws or rules for which there exists no or little relevant guidance from regulators – should not face individual liability if their reasonable interpretation is seen as incorrect with the benefit of hindsight. To this end, we suggest that individual liability should not be used in enforcement actions or settlements intended to introduce a new rule or clarify the interpretation of prior rules.

Did an aggravating factor add to the seriousness of the CCO’s conduct?

As part of generally exercising prosecutorial discretion and conserving agency resources, the SEC does not prosecute every single violation of the securities laws. Around 90 percent of deficiencies identified in examinations are resolved without referral to the Division of Enforcement, let alone a vote by the commission to prosecute. Frequently, situations where an enforcement order or complaint is approved by the commission involve one or a multitude of aggravating factors outside the actual substantive violation – some of which are not publicized in the enforcement order ultimately released if the parties reach a settlement. We believe that cases against CCOs, and most certainly the cases relating to Wholesale Failures, should have such aggravating factors present. Such aggravating factors may include that the CCO already had a deficiency or discussion with the SEC about the Wholesale Failure but failed to change course, or that the CCO exhibited clear indicia of intentional conduct, a disregard for the SEC’s regulatory mission, or extreme disregard for the CCO’s responsibilities.

Active Participation in Fraud

CCOs who engage in securities fraud or other violations of the securities laws deserve to be punished, as does any other violator. If an allegation relates to fraud that is not connected to a CCO’s performance of compliance duties (i.e., is not a CCO Conduct Charge), then we do not suggest that the SEC consider any additional factors in its evaluation.

However, if the allegation is a CCO Conduct Charge, then we do believe that some additional pause is warranted in specific situations. The SEC always thoughtfully decides whether to charge each person in relation to a particular alleged fraud. If a CCO is charged in the context of performance of compliance duties, some may wonder whether the CCO simply joined the wrong firm and was too scared about his or her financial future to leave without another job lined up. While it is imperative for CCOs to evaluate a firm’s compliance culture before joining, and CCOs should try to leave firms that do not have strong compliance cultures, there are only so many jobs available at any one time, and it is largely impossible to accurately and comprehensively evaluate a compliance culture before joining a company. Many, perhaps most, employers will assume that a candidate who left a company in the financial industry without another job lined up was fired, pushed out or encouraged to leave, and such a lapse could dramatically affect the CCO’s career for a long time, potentially permanently.

Due to these concerns, if the allegation is a CCO Conduct Charge, we believe the SEC should demonstrate that the CCO’s conduct “added value” in some way to the fraud committed by the firm or the other individuals charged. Regulators should find evidence indicating such facts as that the CCO’s conduct aided the primary violators in avoiding detection, increased the harm to investors or otherwise exacerbated the fraud.

Obstruction Factors

As noted above, the SEC has explained that one of the ways CCOs can be charged is if they obstruct the SEC in an examination or investigation. Regulatory exams and investigations must be able to proceed on the basis of relative mutual trust, and market participants who abuse that trust deserve punishment.

However, the importance of deterrence should also be balanced by a Framework in order to provide greater clarity to the CCO community and foster greater collaboration between regulators and that community. As the SEC has noted, approximately 90 percent of all deficiencies identified on an exam are resolved via the issuance of a deficiency letter, even though, as a technical matter, the SEC could have brought an enforcement action for each one. In the same way, the exercise of discretion for each and every act of obstruction would place CCOs, and more importantly cause them to believe they are placed, in a unique “firing line” of potential enforcement activity given their front-line work with the SEC.

To that end, we believe that, given the unique roles of a CCO under SEC regulations, enforcement discretion should only be exercised in certain situations. Specifically, the SEC should seek to establish evidence, prior to bringing an enforcement action, of one or more of the following:

Were the acts of obstruction or false statements repeated?

Was the obstruction denied when confronted, or did the CCO not immediately reverse course and cooperate?

Did the obstruction relate to a necessary or highly relevant part of the examination or investigation?

Did evidence show other indicia of intent to deceive or disregard for cooperation with the SEC’s regulatory mission?

MITIGATING FACTORS WEIGHING AGAINST A CCO CONDUCT CHARGE

In addition to our belief that there should be certain specific factors present before issuing a CCO Conduct Charge, we believe that regulators should consider mitigating circumstances, described below, to any situation where they are considering bringing an action. The CCO position in general is unique, and competent CCOs must manage uniquely challenging interactions and competing and conflicting goals and messages in the course of trying to ensure the firm’s compliance while retaining good relationships with leaders and others at the firm. The unconstrained threat of liability raises the anxiety of CCOs. As discussed above, we also believe it may decrease the positive impact of CCOs at their chosen firms. We believe that regulators can alleviate these negative effects by laying out a series of mitigating circumstances that will lessen the potential for CCO Conduct Charges and offer a potential path for CCOs to “protect themselves” in their unique roles. To their credit, representatives of regulators have suggested much of the below in other words. Similar to the underlying basis for developing our proposed Framework in general, we simply believe that committing such factors to writing and documenting formal guidance enhances their impact.

We believe that regulators should consider the following mitigating circumstances:

Did structural or resource challenges hinder the CCO’s performance?

Another factor that should be documented and reviewed each time CCO Conduct Charges are considered is the presence or absence of structural barriers at the firm where the CCO is employed. As discussed in the Report, many CCOs face structural barriers to fulfilling their responsibilities, including not being included in decision-making, their opinion not being respected, limited resources and limited access to senior management. Driscoll devoted his November 2020 speech to discussing such factors, and a OCIE Risk Alert[10] also noted deficiencies for firms providing such an environment.

CCOs appreciate the attention such releases have brought to the matter, but in addition to threatening firms that impose structural barriers, the SEC should mitigate consequences for CCOs faced with such situations. Specific structural or resource challenges that CCOs may face, and that the SEC should consider as mitigating factors, include whether the CCO: (1) maintains a position in the organization that is inferior to that of other similar control functions (e.g., chief information officer, chief human capital officer, chief legal officer); (2) is directly involved with or provided the opportunity for input into material strategic and operational decisions; (3) has sufficient authority to make decisions that could have prevented the alleged misconduct; or (4) maintains adequate resources. Investigations leading to CCO Conduct Charges should determine whether the firm is providing the CCO with resources, appropriate access and decision-making authority and yet the CCO is still being derelict to the appropriate standard. We believe that regulators are, unofficially, already determining such matters in their investigations. As noted in the Report, decisions such as Pennant Management[11] indicate that the SEC will decline to issue charges against a CCO when the circumstances have revealed such barriers. However, we believe that such a factor should be crystallized into a Framework to help fulfill the larger goals of the Framework document.

Did the CCO at issue voluntarily disclose and actively cooperate?

Financial regulators should consider whether the CCO detected or disclosed compliance failures as part of his or her firm’s compliance program, cooperated with regulators, and assisted in remediating the relevant institution’s procedures or conduct. Imposing individual liability on CCOs is not likely to have the intended deterrent effect if liability is imposed on CCOs who work proactively to remediate compliance failures, including by disclosing such failures to regulators as appropriate. Accordingly, many regulatory and enforcement bodies, such as the DOJ and the SEC, have expressly identified disclosure, cooperation and remediation as relevant factors when evaluating prosecutorial decisions.[12] For the same reasons, CCOs should be incentivized to report promptly, remediate and, as appropriate, cooperate with regulators in the event of a compliance failure. However, enforcement actions to date have largely credited remediation efforts in the context of an institution, not an individual CCO.

Were policies and procedures proposed, enacted or implemented in good faith?

Financial regulators should consider whether a written policy or procedure concerning the alleged misconduct existed and whether compliance with that policy or procedure was monitored regularly, or alternatively, whether the CCO drafted strong policies and procedures, but senior business management rejected the policies or failed to provide an adequate budget for implementation. Individual liability will not have the intended effect when imposed on CCOs who reasonably carried out their duties. As a result, whether appropriate procedures existed and whether compliance with those procedures was monitored are highly relevant factors to be evaluated when attempting to distinguish between an unfortunate but good faith compliance failure and a failure resulting from culpable conduct.[13] As indicated by statements from the SEC, policies need not be formalized or in a central document in order to be effective or be evidence of good faith efforts. Moreover, similar to the comment with regard to remediation, regulators should ensure that this factor is not used against a CCO by an institution to blame the compliance function for a business failure.

OTHER PROPOSALS

We also believe that a significant way regulators and CCOs can continue to improve their relationship and effect shared goals is through increased and improved transparency and communication between them. Regulators have made significant strides in this regard in recent years, most notably: (i) the Compliance Outreach Program events conducted regularly by the SEC’s national and regional offices; (ii) speeches and other communications from commissioners and senior staff; and (iii) the recent Risk Alert relating to the compliance function.

However, we believe, parallel to the basis for our proposed Framework as a whole, that more concretized action remains necessary, specifically the following two ideas:

Additional Details Regarding Enforcement Actions

Most SEC enforcement actions that are settled prior to release, including CCO Conduct Charges, are relatively short and appear focused on the minimum facts and analysis necessary to indicate why an action was pursued. We fully appreciate why this may be so, one reason possibly being that respondents negotiate to avoid additional details.

We believe that the SEC should disclose additional details in CCO Conduct Charges where possible. The benefits to respondents of settling in advance remain, even if additional details are included. Further details would help the CCO community understand the SEC’s expectations, as well as appreciate the care we know the SEC already takes before initiating a CCO Conduct Charge, improve CCO morale, and improve the CCO function for the betterment of firms, their investors/clients and regulators alike.

Creation of a Compliance Advisory Committee or Other Formal Ongoing Communication Mechanism

Given the importance of CCOs to regulators, as expressed by commissioners and senior staff many times in recent years, we believe it is appropriate at this time to create a formal ongoing method of dialogue between the compliance industry and regulators. Such an advisory committee would elect members and meet on a set schedule to discuss issues of mutual concern, significant new compliance/regulatory topics and ways that regulators and CCOs can work together for mutual benefit and the benefit of the investing public. We believe that the SEC would benefit from creating and interacting with a compliance-focused group rather than folding such a group into an existing group, such as the Asset Management Advisory Committee, as CCOs have perspectives, concerns and insights that are different in kind from those presented by businesspeople or legal personnel at asset management firms. Such a group would help demystify regulators to compliance industry participants and provide a mechanism for those in the industry who are too anxious to approach regulators themselves to have representatives do so. It would also provide regulators with helpful feedback outside the traditional channels, such as comment letters, which typically only attract interest from a certain, small percentage of CCOs.

CONCLUSION

We thank you for the opportunity to address the important issue of CCO liability. We believe that instituting a Framework, along the lines of the suggestions noted above, is an important and necessary step that would benefit the SEC, the financial industry, the investing public and the capital markets in general, given the unique place that the compliance profession has in the securities regulation regime in the United States.

Footnotes

[1] This proposal does not discuss the unique concerns of CCOs in the banking sector, or regulatory oversight of that function by regulators focused on the banking sector such as the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, or the Federal Reserve. Similarly, it does not discuss the unique concerns of CCOs or regulatory oversight of swap dealers or major swap participants or other categories of registrants by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission or National Futures Association (or security-based swap dealers or major security-based swap participants by the SEC and FINRA, when and where applicable).

[2] Several of the factors we believe the SEC should consider before charging CCOs have parallels to those the SEC and other regulators consider when deciding whether to open investigations, bring charges, and reward cooperation, generally. For example, among other things, the SEC considers “programmatic goals” when determining whether suspected misconduct is serious enough to warrant opening an investigation. Div. of Enforcement, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm., Enforcement Manual, 16 (2017) (SEC Enforcement Manual). As described below, this is an even more important consideration for determining whether to investigate and charge a CCO.

[3] Hester M. Peirce, Comm’r, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Speech at 2020 National Society of Compliance Professionals National Conference (Oct. 19, 2020), available at https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/peirce-nscp-2020-10-19. (All websites cited in this proposed Framework were last visited on May 14, 2021.)

[4] Peter Driscoll, Director, Office of Compliance Inspections and Examination, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Speech at National Investment Adviser/Investment Company Compliance Outreach 2020 (Nov. 19, 2020), available at https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/driscoll-role-cco-2020-11-19.

4 Thaddeus J. North, Sec. Exc. Act. Rel. No. 84500 (Oct. 29, 2018), available at https://www.sec.gov/litigation/opinions/2018/34-84500.pdf.

[6] Id. Under its cooperation framework, in determining whether to charge a cooperator, the SEC, among other things, assesses the severity of the individual’s misconduct and his or her culpability, including whether the individual acted with scienter. SEC Enforcement Manual at 97.

[7] See Blackrock Advisers, LLC, Inv. Adv. Act Rel. No. 4065 (Aug. 6, 2015), available at https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2015/ia-4065.pdf (a CCO participated in multiple meetings regarding a potential disclosure of conflict of interest at issue and sought advice of outside counsel).

[8] Another factor the SEC considers when determining whether to open an investigation and bring charges generally is “the magnitude or nature of the violation.” SEC Enforcement Manual at 15.

[9] Sands Brothers Asset Mgmt., LLC, Inv. Adv. Rel. No. 4274 (Nov. 19, 2015), available at https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2015/ia-4274.pdf .

[10] OCIE Risk Alert, OCIE Observations: Investment Adviser Compliance Program (Nov. 19, 2020), available at https://www.sec.gov/files/Risk%20Alert%20IA%20Compliance%20Programs_0.pdf.

[11] Pennant Mgmt., Inc., Inv. Adv. Rel. No. 5061 (Nov. 6, 2018), available at https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2018/ia-5061.pdf.

[12] For example, under its cooperation framework, the SEC also considers: (i) whether the individual took steps to prevent the violations from occurring or continuing, such as notifying the SEC or another appropriate law enforcement agency of the misconduct or, in the case of a violation involving a company, notifying members of management not involved in the misconduct, the board of directors or an equivalent body not involved in the misconduct, or the company’s auditors of the misconduct; (ii) the assistance provided by the individual, including, among other things, the value and timeliness of the cooperation, the quality of the cooperation, such as whether the cooperation was truthful, complete and reliable, the time and resources conserved as a result of the individual’s cooperation, and the nature of the cooperation, such as the type of assistance provided; and (iii) the efforts undertaken by the individual to remediate the harm. SEC Enforcement Manual at 97. Similarly, the DOJ may consider an individual’s willingness to cooperate in deciding whether prosecution should be undertaken and how it should be resolved. Dep’t of Justice, Justice Manual, §§ 9-27.230, 9-27.420.

[13] Similarly, when determining whether to bring charges against a company, the SEC and DOJ evaluate the adequacy and effectiveness of a company’s compliance program at the time of the alleged misconduct. Both agencies recognize that “a company’s failure to prevent every single violation does not necessarily mean that a particular company’s compliance program was not generally effective.” Crim. Div., U.S. Dep’t of Justice & Enforcement Div., U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm., FCPA: A Resource Guide to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, 57 (2012).